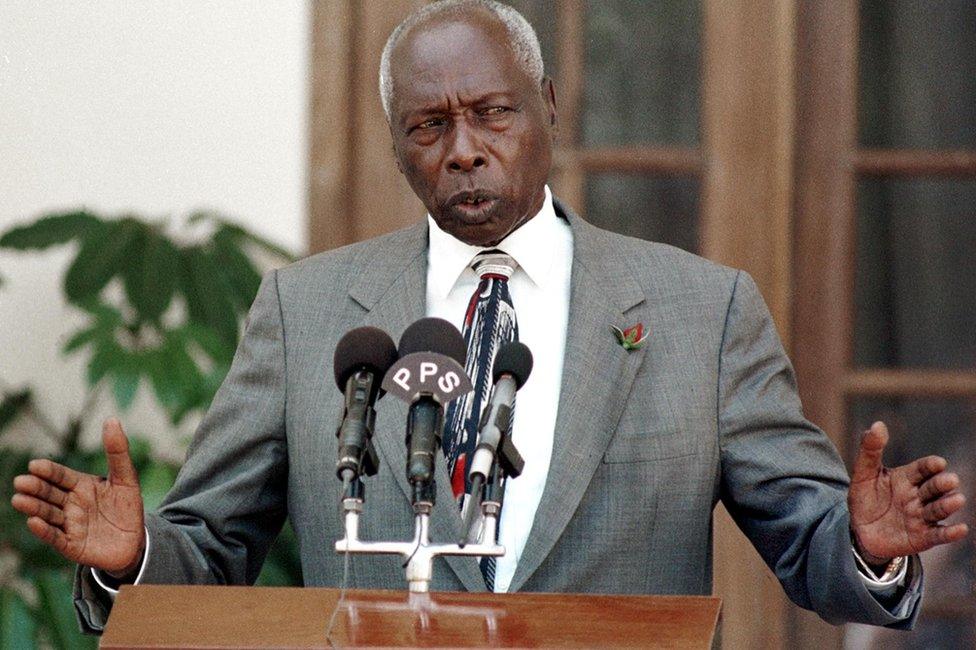

- Moi was everywhere: in the opening paragraph of the news, on the front pages of newspapers, in schoolbooks, on money, and in every classroom through the famous Nyayo portrait. Even billboards bore his message: “Fuata Nyayo” follow in the footsteps.

If you were a child of the '80s or '90s in Kenya, you probably remember how every evening at exactly 7:00 pm, families would gather around the television or radio not just to hear the news, but to first hear about the president.

The familiar phrase “Mtukufu Rais wa Jamhuri ya Kenya, Daniel Toroitich arap Moi...” marked the beginning of the broadcast.

It didn’t matter what the biggest story of the day was whether it was a drought, a school strike, or a scandal the news bulletin always began with the president. Even if all he did was plant a tree or wave at a crowd, that moment made it to the top of the bulletin. It was more than routine it was a ritual.

This was the Moi era, a time when statecraft, media, and personality cult merged into a single televised performance. The Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (then Voice of Kenya — VOK) was the primary outlet, and the media landscape was tightly controlled.

The president’s activities were given the kind of reverence usually reserved for royalty. No matter how minor the event, his coverage always came with the full title, long applause, and sometimes, even patriotic background music.

Read More

To the younger generation, this might sound strange even excessive. But to many who lived through it, it was simply normal.

Moi was everywhere: in the opening paragraph of the news, on the front pages of newspapers, in schoolbooks, on money, and in every classroom through the famous Nyayo portrait. Even billboards bore his message: “Fuata Nyayo,” translating to - follow in the footsteps.

The media didn’t just report on the president they framed national life around him. Development was “because of Moi.” Schools were built “under the guidance of Moi.” Peace rallies, church visits, and cattle dips were all credited to His Excellency.

Editors had to tread carefully, and journalists knew better than to leave the president out of the lead story.

In a sense, it wasn’t just a news structure it was political choreography. The state controlled the narrative, and the people were conditioned to view the presidency not just as a political office, but as the central pillar of daily life.

Things have changed since then. Today, presidents are criticized in real-time on social media, news outlets operate with more independence, and bulletins often lead with hard-hitting headlines not just presidential handshakes.

Yet, for those who lived through the Moi years, that opening line still echoes in memory: “Rais wa Jamhuri ya Kenya, Daniel Toroitich arap Moi...” It reminds us of a time when power wasn’t just held — it was performed, televised, and unquestioned.